For the Queering Popular Culture course at the University of Sussex, I wrote the following paper. It was presented to my tutor, Andy Medhurst, on 19 April 2010 in partial completion of my current MA, and is presented here for interested parties to read, but it remains my personal intellectual property. Its creation was spurred by my personal investment as a gay man in the musical Wicked; it is my attempt to explain that investment.

Following the Legacy of Oz: From Judy Garland to Idina Menzel, Wicked and the Gay Male Audience

“I want to remember this moment. Always. Nobody’s staring. Nobody’s pointing. For the first time, I’m somewhere… where I belong.

-Elphaba (qtd in Cote 155)

The typifying gesture of camp is really something amazingly simple, the moment at which a consumer of culture makes the wild surmise: ‘What if whoever made this was gay too?” […] What if: “What if the right audience for this were exactly me?”

-Eve Sedgwick (qtd in Clum 8 )

Pursuing such questioning, finding the camp and queer elements in musical theatre, is far from difficult, as John Clum states simply, “[M]usicals are camp” (7). He explains, “Musicals were always gay. They always attracted a gay audience, and, at their best, even in times of a policed closet, they were created by gay men” (9). Nevertheless, Stacy Wolf’s recent work on the Broadway musical Wicked[1], while showing the musical to represent the two female leads, Elphaba and G(a)linda[2] as “a queer couple” (“Queer” 5), pays little, to no, attention to the musical’s potential resonances with a gay male audience; she prefers instead to focus on its significant impact on its female audience. Yet, in considering the various cultural discourses and source texts from which Wicked draws, many of which involve the concept of the diva, which historically has been central to the “allure of musical theatre” (Clum 10) for gay men, one hopes, working from Wolf’s findings, to show Wicked open to a discourse involving gay men as much as their sisters.

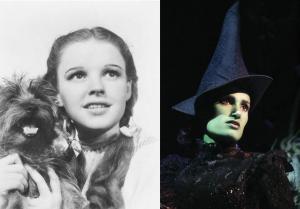

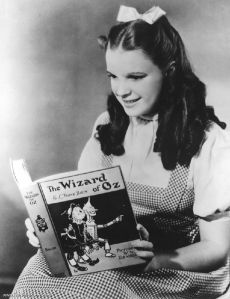

Camp, critically, “allows gay spectators to find gayness in shows that are ostensibly heterosexual and heterosexist. It allows them to identify with the indomitable, odd women, [the] ‘admirable freaks,’ [the divas,] who were often at the center of musicals” (Clum 8). Yet, importantly, such women have been present, not only, as we will discuss later, in this newest incarnation of the Oz tale, but they have been there since its very inception. Also, while the seminal film version of The Wizard of Oz, “serves as [a] pop-culture icon of twentieth-century Western gay culture” (Pugh 217) and the “gay national anthem is still ‘Over the Rainbow’ (Clum 10), before examining the film and the culture of its production, which, undoubtedly, greatly influenced the creation of Wicked, we find, in L. Frank Baum’s original Oz series, the “roots of Oz’s queerness” in its life as a series of children’s fairy tales” (Pugh 218).

Theorist Tison Pugh terms Baum’s Oz a “queer utopia” in which “numerous characters, places, and even objects […] are passingly described as queer” (218). While the literal use of the word “queer” “is decidedly asexual, and Baum typically uses in its connotative sense of odd, unconventional, and eccentric” (219) such as when he calls the Munchkins “the queerest people [Dorothy] had ever seen” or describing the Scarecrow with his “queer, painted face” (qtd 218). Yet, at the same time, “[e]ccentricity and singularity are privileged cultural values in Oz” (219) such as when the Scarecrow encourages Jack Pumpkinhead, who fears ridicule, to embrace his uniqueness, saying, “That proves you are unusual… and I am convinced that the only people worthy of consideration in this world are the unusual ones. For the common folks are like the leaves of a tree, and live and die unnoticed” (qtd in 220). Pugh believes such “privileging [of] the exceptional over the everyday… resounds with metaphorical meaning [for] queer readers [who] could readily apply this moral to their own sense of separation from the dominate heterosexual culture” (220).

Oz, significantly, is filled with admirably freaky women as well. While Dorothy is, of course, the most prominent character in the Oz series, alongside her through much of the series is the fairy princess Ozma, who rules over Oz after the Wizard leaves. Ozma further queers Oz through her personal history; Ozma is introduced in the books as a boy named Tip, raised by an evil crone, “before learning her true identity as a fairy queen” (Pugh 221). After initially resisting the transformation from orphan boy to young princess, he/she eventually accepts, and rules as queen, becoming, “the loveliest Queen the Emerald City have ever known; and although she was so young and inexperienced, she ruled her people with wisdom and justice” (qtd 221). In Ozma we see “the ways in which sexual roles are so readily transmuted in the odd world of Oz” (221). Ozma, however, is not alone in her gendered metamorphosis, “additional examples of gender switching abound in Oz” (221) and, further, “it is within the magical abilities of many creatures to turn themselves into the other sex” (222).

This sexual shifting also grossly impacts Oz’s representation of personal identity and gender as “male activities are often performed by women, notably in the many female armies that march about the country” (223). Further, these female armies are “consistently depict[ed] as more successful soldiers than men, and female troops appear better capable of serving militarily than male troops in many of the Oz books” (224). In this way, ‘[t]he queer utopia of Oz delights in inversions of gender roles” and women are vested with “impressive feats throughout the narratives” (224).

While Oz is populated by a great many strong women, important to the queer reader, it also places an emphasis on homosocial intimacy, “repeatedly evidenced by the deep friendship between the Tin Woodman and the Scarecrow” (Pugh 226). Pugh further explains, “If any couple in the Oz series models the heartfelt affection of a long-term relationship, it is these two fast friends” (226). The Scarecrow represents the relationship as an enduring commitment, “‘I shall return with my friend the Tin Woodman,’ said the stuffed one, seriously. ‘We have decided never to be parted in the future’” (qtd in Pugh 226). Later in the series, the depth of their relationship is described further, “There lived in the Land of Oz two queerly made men who were the best of friends. They were so much happier when together that they were seldom apart” (qtd in Pugh 226). While Pugh concedes, “In this passage, the queerness of the two men is located in their bodies constructed of tin and straw, […] their relationship likewise establishes them as a unique pairing in Oz” (Pugh 226); one, the text seems to suggest, to be valued and emulated.

Out of this queer Land of Oz came the now classic 1939 MGM film, The Wizard of Oz, from which Wicked undoubtedly garners some of its popularity (“Queer” Wolf 4). Further, “Wicked self-consciously poaches lines from the film” (4). For instance, when Nessarose, Elphaba’s sister, asks, “What’s in the punch?” the munchkin, Boq, answers, “Lemons, and melons, and pears,” to which Nessarose replies, “Oh my!,” while later in the musical, Elphaba returns home to visit her sister, quipping, “Well, there’s no place like home!”[3] Each of these references, it is interesting to note, are taken as levity by the audience and recognized as direct references to the source text.

References to the film, however, are not purely textural; G(a)linda first enters the stage via a steel orb surrounded by a sea of soap bubbles, reminiscent of the bubble in which Glinda first enters in the film (“Queer” Wolf 4), while various set details also make clear nods toward the film, including, “the iconic yellow-brick-road and the fallen Kansas house with the Wicked Witch of the East’s stripped stockings and ruby-slippered feet poking out” (4).

While the film is “one of America’s most well-known and beloved tales” (4), The Wizard of Oz is also taken by many as “an allegory of gay experience” (Clum 153), with a lasting impact on gay culture. Clum writes of the connection,

[G]ay life is seen as a technicolor Oz, far away from the oppressive, homophobic black-and-white world in which many gay men were raised. Oz has dangers, as does living in the urban gay ghetto, but they’re mitigated by the fabulousness of the place. There Dorothy and her queer friends can build their own family. (10-11)

Clum, of course, is far from alone in acknowledging the film as gay culture’s “seminal work” (10), as Pugh explains, “With Judy Garland as the star, its exaggerated characters of good and evil, and its Technicolor wonderland of vibrant colors and outlandish costumes, the film displays a queer sensibility that countless viewers adore” (217). Clearly, as Alexander Doty has written, gay men, even as children, have an intense relationship with the film. Doty, recounting his own childhood, wrote:

[A]s a kid, I loved Dorothy, loved Toto, was scared of, but fascinated by, the Wicked Witch of the West, felt guilty for thinking good witch Glinda was nerve-gratingly fey and shrill, thought the Tin Man was attractive and the Scarecrow a big showoff [and] I was really embarrassed by the Cowardly Lion. (49)

These identifications, Doty argues, change for gay men over time. He recounts:

[I]n my twenties I became aware of butches and of camp, both of which fed into my developing ‘gay’ appreciation of The Wizard of Oz. Camp finally let me make peace with the Cowardly Lion. He was still over-the-top, but no longer a total embarrassment. […] King of the Forest? He was more like a drag queen who just didn’t give a fuck. (50)

While the film, clearly, has been read as retrospectively camp by many gay men, as camp, itself, has been “largely understood as a reception practice [it also] may be invoked as a production practice to understand stylistic influences in musical films produced at MGM by the Feed Unit” (Tinkcom 24) by which the production of Oz was influenced. While the Freed Unit, a film unit within MGM populated, largely, by gay men, famous for the production of its most lavish movie musicals (26), did not come into being until after the film’s production (24), Arthur Freed, later to become head of the unit, did work as an uncredited producer on Oz, along with many of his future collaborators, who came to be mockingly referred to as both “Freed’s Fairies” (Clum 148) and “the royal family” (26) by others at MGM. The group of producers, directors, and, largely, art directors, helped to craft the “dazzling sets, costumes, use of color […] and choreography” (Tinkcom 34) all paramount in realizing the fantastic Land of Oz. Additionally, gay director George Cukor, most famous for having directed Gone With the Wind, and, later, Judy Garland’s A Star is Born spent a few days on the Oz set after its first few weeks of principal photography. Appalled at the film thus far, finding the film lacking the “child-like quality” (Haley) it needed, Cukor set to work, altering make-up and costumes for many of the principles. Cukor “particularly dislike[d] Judy Garland’s appearance. He [took] off her curly blonde wig and half of her make-up” and, critically, he told her to “remember, you’re just a little girl from Kansas” (Haley). Such alterations, however seemingly slight at the time, effectively created the iconic image of Dorothy we have today (Haley).

Not only did a gay man effectively craft the image of Dorothy, but the principle films produced by the Freed Unit in the ensuing decade were, among others, Meet Me in St. Louis (1944), The Clock (1945), The Harvey Girls (1946), The Pirate (1948), and Easter Parade (1948), all of which, incidentally, were star vehicles for Judy Garland (Clum 148). Gay men, it can be argued, crafted what we take today as “Judy Garland;” “Garland’s screen image was nurtured by gay men[;] [s]he was the diva of the Freed Unit” (Clum 148). They “mentored, directed, choreographed, and costumed her, in effect, shaping her distinct performing style to achieve its camp register” (295). Paramount among these, early in her career, before Vincente Minnelli, who was “widely known as homosexual within the small circuit of Hollywood” (Tinkcom 31) yet, nevertheless, would become Garland’s second husband, and father to Liza, was Roger Edens who worked with Garland as early as 1936 to craft her voice into the sound we recognize today (Cohan 295). In this way, Garland is, at least in part, a gay creation, the most famous of those “indomitable, odd” divas at the center of the classic Hollywood musical (Clum 8).

If Garland’s image was shaped by gay men, it makes sense that that same image would then resonate with them; the way in which Garland is often portrayed in the MGM films as the best-friend to the leading man, and not, of course, his love interest, or placed in close proximity to more beautiful, glamorous women, who come closer to the expectations of exuding sexuality than Garland could ever hope. Next to such women, Garland must have felt inferior and inadequate, much like some gay men who are uncomfortable with, but expected to enjoy, the company of the straight men around them. Garland experienced this in several films, but most pointedly perhaps when she was placed in the company of both Hedy Lamarr and Lana Turner in 1941’s Ziegfeild Girl. In viewing the film it becomes painfully clear that Garland “does not have and cannot carry off glamour” (Dyer 163). Garland’s Oz co-star Ray Bolger said of her, “She wasn’t pretty; she was plump. But, in a way, she was beautiful” (Haley).

Yet, as Richard Dyer writes, the connection between gay men and Garland only intensified later, after 1950, when she was sacked by MGM and, subsequently, tried to commit suicide. Doing so caused “a sudden break with Garland’s uncomplicated and ordinary MGM image [which] made possible a reading of Garland as having a special relationship to suffering, ordinariness, normality, and it is this relationship that structures much of the gay reading of Garland” (138). Importantly, this “post-1950 reading was also a reading of her career before 1950, a reading back into the earlier films […] in the light of later years” (139) which, as has already been noted, were rich in a direct gay influence. Dyer notes, in looking at what many gay men have written about Garland, they “stress [her] emotionality and its relation to the situation of gay men” (141). Central to most of these accounts are, beyond her emotionality, Garland’s seeming ability to recover after setbacks, and the strength she displayed through her suffering. Of her emotionality, Roger Woodcock, in the first issue of Jeremy, “an ostensibly bisexual publication, which appeared just before the development of the gay liberation movement in Britain,” (141) wrote, “Every time she sang, she poured out her troubles. Life had beaten her up and it showed. That is what attracted homosexuals to her. She created hysteria for them” (qtd in 141). Barry Conley, writing for Gay News, outlined Garland’s appeal to gay men, citing her ability to fight back from disappointment. He wrote,

She began to gather a large following of homosexuals at her concerts, who were eager to applaud each and every thing she did… Perhaps the majority of those audiences saw in Judy a loser who was fighting back at life, and they could themselves draw a parallel to this. (qtd in Dyer 142)

These quotes show, while “Garland is often painted as a pathetic figure and her fans – particularly her gay fans – as devotees of disaster […] the true attraction to Judy Garland [is] her indomitable spirit, not her self-destructive tendencies, that appeals to gay audiences” (qtd in 142). Another of Dryer’s commentators made this point directly, and inphatically; he wrote,

I loved her because no matter how they put her down, she survived. When they said she couldn’t sing; when they said she was drunk; when they said she was drugged; when they said she couldn’t keep a man… When they said she was fat; when they said she was thin; when they said she’d fallen flat on her face. People are falling on their faces every day. She got up. (qtd in 142).

While Garland “managed to retain all her ‘straight’ admirers” (142) during her lifetime, even many of them were acutely aware of the gay presence in her audiences, as the reviewer from the Los Angeles Citizen News for her 1961 Hollywood Bowl concert wrote:

They were all there, the guys and dolls and the “sixth men”,[4] sitting in the drizzle which continued throughout the concert… After “Over the Rainbow” the standing, water-soaked audience applauded until Judy came back and sang three more songs. The guys and gals and “sixth man” wanted more. (139-140)

Yet, given the gay male presence in crafting her stage persona, it seems only too appropriate that Garland has come to signify gayness in those who appreciate her. By way of introduction to his chapter on Garland’s fandom, Steven Cohan glibly paraphrases Jane Austen in writing,

It is a truth almost universally acknowledged that a single man in possession of a Judy Garland CD must not be in want of a wife. However little known the feelings or views of such a man may be on his first entering a record store, this truth is so well fixed in the minds of the surrounding public that Garland is considered the rightful property of some one or other of Dorothy’s friends. (287)

While some may see the connection between gay men, the figure of the diva, and Garland as potentially antiquated, and therefore of little impact on the reception of Wicked, Clum wrote of a lingering connection he observed in his own students,

[T]his twenty-year-old goes into a perfect imitation of Ethel Merman doing “You Can’t Get a Man with a Gun.” He is enthusiastically joined by a heretofore quiet freshman sitting twenty feet away. Ethel Merman was not on television or film during these kids’ lifetimes, but they can do Ethel Merman imitations and know all the lyrics to the song. (37)

In assessing the interaction he witnessed, Clum, knowing one student, and strongly suspecting the other to be gay, wrote, “[T]his joint Ethel Merman imitation is a kind of signaling and bonding ritual for the two young men,” he further explains, “This, too, is gay culture, the maintaining of a flamboyant tradition of musical theater and musical divas these kids have never experienced first hand, but somehow know” (37). Some gay men are “doing musicals, and for them doing musicals is in some way part of their gayness” (37).

This same connection between the musical and gayness is never stronger, even today, than around the figure of Judy Garland. Yet, today, this connection is growing controversial,

Garland and the history she stands for are now an embarrassment for a younger generation of gay men who, seeking to assimilate more easily into heteronormative culture, ‘just want to be regular guys – with better-than-average bodies.’ Garland’s remaining fans, in the meantime, are looked down on with ridicule as “Judy queens.” (Cohan 288)

While it may be true that Garland’s fans, and gay fans of musical theatre, may be ridiculed by their fellow gay men, much as straight-acting Will who is “no more flamboyant than most sitcom straight heroes” (Clum 27) criticizes effeminate, musical loving Jack (Clum 28). While the musical/Garland connection with gay men has grown to be “itself[…] an area of contention” (29), it nevertheless seems to prove, enduringly, true. Of course, “[n]ot all gay men are show queen; not all men who love musicals are gay. But there is a phenomenon, the show queen, for whom gayness and musical theater are connected” (38).

Given the strong, and enduring connection between gay men and the musical, a gay male attraction to Wicked is only enhanced by the conventions the musical takes up, utilizes, and queers. The musical, as Wolf has established, “follow[s] the conventions of mid-twentieth-century musical theatre” (“Queer” Wolf 2), conventions greatly influenced by the megamusicals of the Freed Unit. Early in the first act of Wicked following the meeting of its two protagonists, Elphaba, “the smart political outcast” and G(a)linda, “the vapid, popular girl who becomes Glinda the Good Witch,” sing a duet, “What is this Feeling?,” which uses the conventional language of a love song to convey their mutual distain. Composer Stephen Schwartz calls it a “falling into hate” song (Laird 344). Wolf cites the same form of song originally in Oklahoma, “meant to express […] incompatibility” between two lovers (“Queer” Wolf 2). The structure of “What is this Feeling?” leads the audience to think “the pair is singing a queer love song” until it is revealed that the “feeling” is “loathing” (2). The song, “plays with the audience’s expectations […] and renders the song doubly queer” (2), firstly, it “def[ies] conventions of genre because it sounds like an actual love song,” while simultaneously “defy[ing] conventions of gender because it [is] between two women in the resolutely heterosexual form of the musical” (2). Wolf, writing elsewhere on the female duet has stated that such songs “make explicit what the musical represses” (“Always” Wolf 351) namely that Elphaba and G(a)linda “are the show’s central couple” (351). Wolf writes, “a female duet provides a unique timbre […] When two women are heard together, they signify a couple, and two women’s voices, in close proximity as they hit notes within the same octave, creates a particularly intimate aural relationship on which the female duet capitalizes” (358). Such an “erotic charge of such intertwined voices […] is [a] homoerotic jouissance de l’écoute[5]” Given the potential sexual connotations of female duet, and song’s power in musicals to progress the plot and relationships (“Always” Wolf 352), it is significant that Elphaba and G(a)linda, “sing four duets of various tones and tempos over the course of the show” (“Queer” Wolf 12) which is “unusually high for any romantic couple in a musical” (13) which only further “emplot[s] the two women as a romantic couple” (8).

While the musical does, as it must, concern itself with the pretense of a heterosexual romance, in the case of Wicked a love triangle with the two female leads vying for the attention of the male lead Fiyero, “whose part is not even large enough to consider him a principal” (18), even the actors who have played him know “the character merely exists to foreground the women’s strong connection and attachment” (18). Norbert Leo Butz, Broadway’s original Fiyero has said, “[T]he real story is between the two women” (qtd in 18) while David Ayers has said, “Fiyero is a vehicle to tell the story of the two women” (qtd in 18).

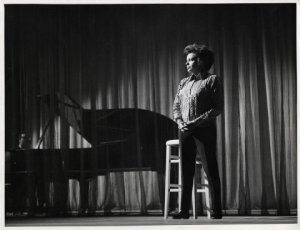

Yet, this is a queer romance, in which its two participants is each a diva in her own right. The diva is, an “extraordinary woman [who] often emerges from the conjunction of an ‘ugly’ exterior and a beautiful, powerful voice” (“Divas” Wolf 46) which perfectly defines Elphaba. She is “a Broadway archetype: the unprepossessing, unlikely creature transformed into a powerhouse whenever she sings” (46). Wicked’s producer Mark Platt makes clear this power of expression, “In a stage musical, you can turn to your audience and sing them exactly what you’re feeling” (qtd in 46); in this way both Elphaba and G(a)linda are “exuberantly self-expressive” (46) in a way very reminiscent of the qualities which drew gay men to Judy Garland, as one gay man wrote of Garland, “In every song I’ve heard it gives you something of her as a person, all of the tragedy and happiness of her life is echoed in every word she sings” (qtd in Dyer 145). Also, similar to Garland, Elphaba sings of “desire for men and of relationships with men going wrong” (151); while Garland sang of “The Man that Got Away,” Elphaba sings of her own inability to have the man she desires in “I’m Not That Girl.”

In some ways, Elphaba “typifies Broadway’s traditional diva: she is the dark, alto outsider who sings the musical’s well-known belting numbers, ‘The Wizard and I’ and ‘Defying Gravity.’ She breaks the rules and is condemned for her strength and determination” (“Diva” Wolf 48). Schwartz has said he “modeled Elphaba on Barbra Streisand […] in Funny Girl” (“Queer” Wolf 12). In “The Wizard and I” Elphaba tells the audience she is “a diva, a visionary, independent, and ambitious” (12), yet, like Judy Garland, “she is a vulnerable girl who wants to be pretty and popular” (12). Not only does Elphaba share traits with Garland, but she also is positioned as a “Dorothy-like heroine” (12) endangering, and ultimately martyring, herself for the sake of her friends. Schwartz goes to pains to make the connection with Dorothy all but explicit; Elphaba’s theme motive, which always hinges on the use of the term, “unlimited,” which is threaded through a number of her songs, contains the exact sequence of six notes that begin Harold Arlen’s main musical line for “Over the Rainbow.”

While Elphaba is more earnest in her desires, G(a)linda “embodies the diva’s excess” (“Diva” Wolf 48), yet she, like her friend, possesses a dual persona with which any queer person, who has at some time been closeted, can find resonance. Schwartz has acknowledged of G(a)linda, she “is, in some ways, two distinct characters: the real woman who is friendly, but insecure and superficial; and the ‘posed’ Galinda who is the beautiful ‘good witch.’” (Laird 343).This dichotomy is reflected in Kristin Chenoweth[6]’s performance of G(a)linda on stage; “as the ‘real’ Galinda, Chenoweth belted; as the public persona, she soared into her upper [soprano] register” (343). In the show’s opening number, “No One Mourns the Wicked” G(a)linda “stages a performance of a performance in her role as a public figure,” in so being, it is sung “in a significantly higher register than any other song in the show” (“Queer” Wolf 12). The song is “Glinda’s only true soprano number; its unusual tessitura confirms the song’s status as public display, as performance” (12). This queer duality of her persona is further made clear in the opening of the second act when, standing on a platform addressing the citizens of the Emerald city, and the audience, G(a)linda is purposely made up with an upswept hairstyle, dress, and arm gestures which make direct visual reference to Andrew Lloyd Webber’s Evita.

The potential resonances gay men find with the divas at the center of Wicked has been found to not simply rest with the characters, but has expanded to include the leading ladies who play them, “each of whom gathers a huge fan following” (“Divas” Wolf 41). Yet, none of these, it could be argued, have accrued a larger following than Broadway’s original Elphaba, Idina Menzel. This following never made itself more visible than at the Broadway Wicked performance on 9 January 2005. It was meant to be Menzel’s final in a role she originated, and for which she earned a Tony Award. Yet, Menzel had been injured “during the previous day’s performance when the elevator beneath the stage into which she ‘melts’ dropped early” causing her to fall through, breaking two ribs (40). On the following evening, at the point at which Elphaba was to reappear on-stage after her ‘melting,’ instead of a trap door opening and Menzel’s stand-by appearing, through a different entrance Menzel herself “walked gingerly from the wings onto the stage, decked out in a red Adidas warm-up suit and red sneakers” (40). Jesse McKinley for the New York Times wrote of that moment “She wasn’t in costume, she wasn’t in makeup, and she wasn’t even in character” yet she received a standing ovation “like few you’ve ever seen: a screaming, squealing, flashbulb-popping explosion that was equal parts ecstatic hello and tearful goodbye” (qtd in 40).

While Wolf claims the show to have a “cult status among tween (pre-adolescent) and teenage girls” (43), which it admittedly does, she makes such a pronouncement, it would imply, at the exclusion of anyone else. Yet, when Menzel, in 2006, decided to return to the role of Elphaba for Wicked’s opening in the West End, more than a few young gay men flew from around to world to see Menzel reprise the role. Such becomes clear when observing the goings on at the stage door after each of Menzel’s performances during her four month residency in London. Amid crowds so thick barricades were erected to maintain order, many young men, myself and young men I knew among them, were present to pay their respects to the diva of Wicked in much the same way young men some fifty years ago routinely stormed the stage to be near, and touch Judy Garland at the end of her concerts (Dyer 140).

If this fandom was ever in doubt, one need only look to a recent episode of Fox’s Glee which saw Kurt, the openly gay, effeminate, member of the show choir, exclaim upon seeing an upcoming set list, “Defying Gravity? I have an iPod shuffle dedicated exclusively to selections from Wicked! This is amazing!” (“Wheels”) The episode then sees Kurt distraught when he is denied permission to sing the song. He goes on to petition the choir-director to permit him to do so, despite the fact it is “traditionally sung by a girl” (“Wheels”). Glee itself openly appeals to not only young girls and women, as would be expected, but fans who identify most strongly with Kurt, particularly in recruiting both Kristin Chenoweth (“Rhodes”) and, more recently, Idina Menzel, (“Hell-O”) in recurring roles on the series. Such young men, who in the past identified with Judy/Dorothy, today identify with Idina/Elphaba and other divas, in their search for “a place where [they] belong” (Colt 155).

[1] The show is billed as “The untold story of the witches of Oz,” and tells the story of the friendship between G(a)linda the Good Witch and, Elphaba, the Wicked Witch of the West and how they both came to be the characters found in the 1939 film (Cote 6).

[2] The good witch’s name shifts from “Galinda” to “Glinda” through the course of the narrative. While this aspect of the musical is irrelevant to this essay, I have chosen to reflect the shift through the use of a composite.

[3] As Stacy Wolf has previously acknowledged, no entire printed libretto of Wicked exists to date. The Wicked souvenir book, Wicked: The Grimmerie, contains only the songs’ lyrics and some extent of the dialogue. Other lines, therefore, have been taken from performance. (A full list of attended performances, to date, can be found in the Works Consulted).

[4] “‘The sixth man’ is a reference to Kinsey’s findings on the incidence of homosexuality in the American male” (Dryer 140).

[5] No comparable English expression exists; it is, roughly, the sound of (feminine) orgasm.

[6] Kristin Chenoweth originated the role of G(a)linda, playing her in workshops, in the San Francisco pre-Broadway run, and on Broadway from October 2003 to June, 2004 (Laird 343).

—-

Works Cited

Clum, John. Something for the Boys. New York: Palgrave, 1999.

Cohan, Steven. Incongruous Entertainment: Camp, Cultural Values, and the MGM Musical. London: Duke University Press, 2005. 285-335.

Cote, David. Wicked: The Grimmerie. New York: Hyperion, 2005.

Dyer, Richard. Heavenly Bodies. 2nd ed. London: Routledge, 2004. 137-191.

Haley, Jack, dir. Wonderful Wizard of Oz: The Making of a Movie Classic. Jack Haley Jr. Productions. Turner Entertainment. 1990. DVD. Warner Home Video: 2006.

“Hell-O.” Glee. Fox. 13 April 2010.

Laird, Paul. “The creation of a Broadway musical: Stephen Schwartz, Winnie Holzman, and Wicked.” Cambridge Companion to the Musical. Ed. William Everett & Paul Laird. Cambridge: Cambridge UP, 2009. 340-352.

Pugh, Tison. “‘There lived in the Land of Oz two queerly made men’: Queer Utopianism and Antisocial Eroticism in L. Frank Baum’s Oz Series.” Marvels and Tales: Journal of Fairy-Tales Studies. 22.2 (2009): 217-239.

“Rhodes Not Taken, The” Glee. Fox. 30 September 2010.

Tinkcom, Matthew. “Working Like a Homosexual: Camp Visual Codes and the Labor of Gay Subjects.” Cinema Journal. 35.2 (1996): 24-42. Print.

“Wheels.” Glee. Fox. 11 Nov. 2009.

Wolf, Stacy. “‘Defying Gravity’: Queer Conventions in the Musical Wicked” Theatre Journal. 60. (2008): 1-21.

—. “‘We’ll Always Be Bosom Buddies’ Female Duets and the Queering of Broadway Musical Theatre.” GLQ: A Journal of Gay and Lesbian Studies. 12.3 (2006): 351-376.

—. “Wicked Divas, Musical Theatre, and Internet Girl Fans.” Camera Obscura. 22.2 (2007): 39-71.

—

Works Consulted

Davis, Reid. “WOZ: Lost Objects, Repeat Viewings, and the Sissy Warrior.” Film Quarterly. 55.2 (2002): 2-13.

Wicked. By Stephen Schwartz and Winnie Holtzman. Dir. Joe Mantello. Music and lyrics by Stephen Schwartz. Perf. Ana Gastyer and Kate Reinders. Ford Center for the Performing Arts: Oriental Theatre. Chicago. 6 January 2006.

Wicked. By Stephen Schwartz and Winnie Holtzman. Dir. Joe Mantello. Music and lyrics by Stephen Schwartz. Perf. Kristy Cates and Stacie Morgain Lewis. Ford Center for the Performing Arts: Oriental Theatre. Chicago. 20 April 2006.

Wicked. By Stephen Schwartz and Winnie Holtzman. Dir. Joe Mantello. Music and lyrics by Stephen Schwartz. Perf. Dee Roscioli and Stacie Morgain Lewis. Ford Center for the Performing Arts: Oriental Theatre. Chicago. 17 May 2006.

Wicked. By Stephen Schwartz and Winnie Holtzman. Dir. Joe Mantello. Music and lyrics by Stephen Schwartz. Perf. Idina Menzel and Hellen Dallimore. Apollo Victoria Theatre. London. 28 October 2006.

Wicked. By Stephen Schwartz and Winnie Holtzman. Dir. Joe Mantello. Music and lyrics by Stephen Schwartz. Perf. Dee Roscioli and Kate Fahrner. Ford Center for the Performing Arts: Oriental Theatre. Chicago. 21 January 2007. 17 August 2007. Matinee.

Wicked. By Stephen Schwartz and Winnie Holtzman. Dir. Joe Mantello. Music and lyrics by Stephen Schwartz. Perf. Dee Roscioli and Erin Mackey. Ford Center for the Performing Arts: Oriental Theatre. Chicago. 17 August 2007. Evening.

Wicked. By Stephen Schwartz and Winnie Holtzman. Dir. Joe Mantello. Music and lyrics by Stephen Schwartz. Perf. Dee Roscioli and Kate Fahrner. Ford Center for the Performing Arts: Oriental Theatre. Chicago. 8 October 2008.

Wicked. By Stephen Schwartz and Winnie Holtzman. Dir. Joe Mantello. Music and lyrics by Stephen Schwartz. Perf. Ashleigh Gray and Dianne Pilkington. Apollo Victoria Theatre. London. 24 October 2009. Matinee.

Wicked. By Stephen Schwartz and Winnie Holtzman. Dir. Joe Mantello. Music and lyrics by Stephen Schwartz. Perf. Alexia Khadime and Dianne Pilkington. Apollo Victoria Theatre. London. 24 October 2009. Evening. 26 November 2009. 3 December 2009. 9 March 2010.

//

//

I’ll be real – I really, really wanted Hillary Clinton to be President of the United States, and that’s not a new feeling. I lived through the 1990s – granted I was a child, but I still remember them, and thinking then that times were good. As a child, it was simply a fact that Bill Clinton was president. It was an immutable fact, not a transitory one. The capital was Washington D.C. and Bill Clinton was the President. On Tuesday evening, I felt much the same way as the returns came in. While Donald Trump and Hillary Clinton had both run for the office, it was, to my mind another immutable fact that Hillary Clinton would be the next President of the United States. Hillary would be President, and she would continue the progressive, supportive work of President Obama. That’s what any rational person would want, and I had to believe there were more good people in America than narrow-minded ones.

I’ll be real – I really, really wanted Hillary Clinton to be President of the United States, and that’s not a new feeling. I lived through the 1990s – granted I was a child, but I still remember them, and thinking then that times were good. As a child, it was simply a fact that Bill Clinton was president. It was an immutable fact, not a transitory one. The capital was Washington D.C. and Bill Clinton was the President. On Tuesday evening, I felt much the same way as the returns came in. While Donald Trump and Hillary Clinton had both run for the office, it was, to my mind another immutable fact that Hillary Clinton would be the next President of the United States. Hillary would be President, and she would continue the progressive, supportive work of President Obama. That’s what any rational person would want, and I had to believe there were more good people in America than narrow-minded ones.

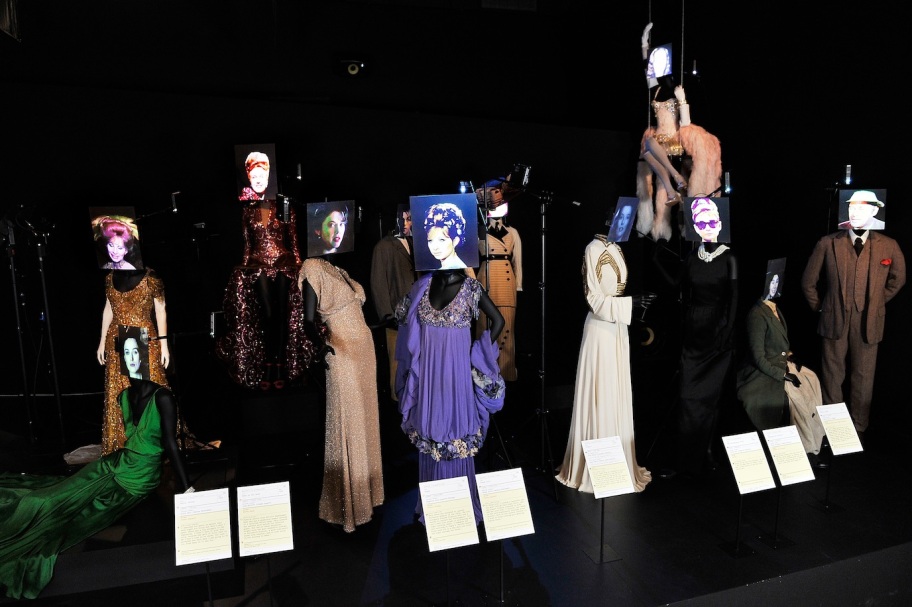

Walking into the exhibition, you’re confronted by a cinema screen as wide as the exhibition room itself, showing short film clips, each focusing on a costume piece in the collection, with a sweeping score seducing you into the darkened cinematic galleries. Indiana Jones, Dorothy Gale, Mildred Piece, Scarlett O’Hara (and others) appear in quick succession. As someone absolutely enamored of film costumes (none more so than a certain pair of little red shoes), I’d been excited for this day ever since an announcement of the exhibition had appeared in the auction catalog for the sale of Debbie Reynolds collection in the summer of 2011. I thought it would be an amazing day, looking at all these fantastic works of art. But, I wasn’t prepared for what they would make me feel.

Walking into the exhibition, you’re confronted by a cinema screen as wide as the exhibition room itself, showing short film clips, each focusing on a costume piece in the collection, with a sweeping score seducing you into the darkened cinematic galleries. Indiana Jones, Dorothy Gale, Mildred Piece, Scarlett O’Hara (and others) appear in quick succession. As someone absolutely enamored of film costumes (none more so than a certain pair of little red shoes), I’d been excited for this day ever since an announcement of the exhibition had appeared in the auction catalog for the sale of Debbie Reynolds collection in the summer of 2011. I thought it would be an amazing day, looking at all these fantastic works of art. But, I wasn’t prepared for what they would make me feel.

As a child, I loved nothing more than to sit down with a Classical Hollywood film, and many I’m not ashamed to admit I’ve seen dozens of times. So, for me, they really did feel something like old friends and, to see the clothes many of those characters in my imagination wore, well, it touched me deeply. For those who love movies, we carry those characters, and their stories, with us, and, thankfully for us, we can visit them whenever we wish.

As a child, I loved nothing more than to sit down with a Classical Hollywood film, and many I’m not ashamed to admit I’ve seen dozens of times. So, for me, they really did feel something like old friends and, to see the clothes many of those characters in my imagination wore, well, it touched me deeply. For those who love movies, we carry those characters, and their stories, with us, and, thankfully for us, we can visit them whenever we wish.

![george-clooney-and-brad-pitt-perform-at-star-studded-gay-marriage-play-8-reading[1]](https://thethingthatreadsalot.files.wordpress.com/2012/03/george-clooney-and-brad-pitt-perform-at-star-studded-gay-marriage-play-8-reading1.jpg?w=300&h=199)

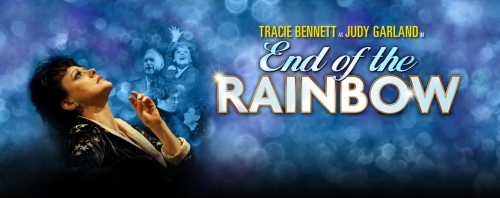

While Mickey clearly is, at first, trying his best to get her off the medications and alcohol, eventually he relents, both so she isn’t in pain for a few brief moments, and seemingly more importantly, so she can go back out on stage, in an effort to ease some of her debts. (Garland would, in fact, die almost $4 million in debt.) Only later do we see her continue to struggle, dealing with the ensuing upset and illness the medications must have caused again and again, despite everyone’s efforts.

While Mickey clearly is, at first, trying his best to get her off the medications and alcohol, eventually he relents, both so she isn’t in pain for a few brief moments, and seemingly more importantly, so she can go back out on stage, in an effort to ease some of her debts. (Garland would, in fact, die almost $4 million in debt.) Only later do we see her continue to struggle, dealing with the ensuing upset and illness the medications must have caused again and again, despite everyone’s efforts. Here the play leaves us, with Anthony giving a brief epilogue, telling of Judy’s brief marriage, death, and funeral, followed by Bennett’s haunting rendition of the second half or so of ‘Over the Rainbow,’ reminding us, that, despite it all, Judy Garland is still very much with us. She is Dorothy, and she always will be. Judy’s final words are these, “Immortality would be nice. Yes I’d like that. Immortality might just make up for everything.” While the hardships she endured can never be erased, I like to think she would be pleased to know that over forty years after her death, while many may not know her name, people of every age, still hold Dorothy close to their hearts, and as long as they do, she is still, very much, with us.

Here the play leaves us, with Anthony giving a brief epilogue, telling of Judy’s brief marriage, death, and funeral, followed by Bennett’s haunting rendition of the second half or so of ‘Over the Rainbow,’ reminding us, that, despite it all, Judy Garland is still very much with us. She is Dorothy, and she always will be. Judy’s final words are these, “Immortality would be nice. Yes I’d like that. Immortality might just make up for everything.” While the hardships she endured can never be erased, I like to think she would be pleased to know that over forty years after her death, while many may not know her name, people of every age, still hold Dorothy close to their hearts, and as long as they do, she is still, very much, with us.